Tutorial: Build a Network Sniffer From Scratch

-

A network sniffer allows you to intercept, log and analyze network traffic.

In this tutorial we will build one from scratch in python3, using only standard libraries.

If you are just looking for a good sniffer, then you should probably use tcpdump (terminal) or Wireshark (GUI). We are kind of reinventing the wheel here. The point of this tutorial is to take a (somewhat) deep dive into the network stack.

If you have fun building things yourself, or if you like to be able to turn every little knob, then this program-along tutorial is for you.

I expect you to have a basic understanding of the ISO/OSI (or TCP/IP) network model and beginner tier Python3 skills. We will write this application on Linux since it gives us greater freedom when it comes to sniffing low level traffic.

Ingredients

All we really need for this is access to a raw socket. Which the Python3 socket API happily provides us with (requires root priviliges):

import socket

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_RAW, filter)

You will notice the third parameter filter, which determines which kind of packets we will receive from the network interface.

If you are on Linux, then a quick look into /usr/include/linux/if_ether.h gives us a list of the available values for this filter. Under the section "Non DIX types..." we find the following:

#define ETH_P_802_3 0x0001 /* Dummy type for 802.3 frames */

#define ETH_P_AX25 0x0002 /* Dummy protocol id for AX.25 */

#define ETH_P_ALL 0x0003 /* Every packet (be careful!!!) */

#define ETH_P_802_2 0x0004 /* 802.2 frames */

#define ETH_P_SNAP 0x0005 /* Internal only */

#define ETH_P_DDCMP 0x0006 /* DEC DDCMP: Internal only */

#define ETH_P_WAN_PPP 0x0007 /* Dummy type for WAN PPP frames*/

#define ETH_P_PPP_MP 0x0008 /* Dummy type for PPP MP frames */

#define ETH_P_LOCALTALK 0x0009 /* Localtalk pseudo type */

#define ETH_P_CAN 0x000C /* CAN: Controller Area Network */

#...

For our purposes we will use ETH_P_ALL 0x0003. And of course we promise to be careful ;)

ETH_P_ALL = 0x03

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

Getting access to a raw socket on Windows is a bit more complicated, so we will work on *nix for now.

Struct

For plucking apart the bytes that we will receive we can use another Python3 standard library called struct.

import struct

data = bytes([0x01, 0x02, 0x03, 0x04, 0x05, 0x06, 0x07, 0x08])

SOURCE, DEST, LEN, CHKSUM = struct.unpack("! H H H H", data[:8])

This example snippet takes 8 continous bytes as input and returns 4 individual short values.

The exclamation mark ! tells struct that we want to work with network byte order (Big Endian).

For an unsigned byte we use B

For an unsigned short (two bytes) we use H

For an unsigned integer (four bytes) it is I

For an unsigned long long (eight bytes) it is Q

You can also snip off an odd number of bytes by using 6s, which would return 6 bytes as a Python3 bytes object.

The lowercase variants b, h, i and q are the signed versions, which we won't really use in this tutorial.

Layers

If you remember your network class, the abridged OSI network model looks somewhat like this:

- Physical Layer

- Data Link

- Network

- Transport Layer

- Session and Application Layers

Wherein the data is transmitted and received by the physical hardware on layer 1 and then moves it way up through the various layers until it eventually reaches the user at the highest layer.

We will work our way up from the second Layer to the fourth Layer and look at:

- Ethernet Frames (L2)

- IPv4 Packets (L3)

- TCP Segments and UDP Datagrams (L4)

I have excluded IPv6 for simplicity's sake (but it should be easy for you to implement that yourself afterwards).

The reason why we start at such a low level is that we will look at ARP (L2 & L3) and similar protocols in later tutorials.

L2: Ethernet

If we check the wikipedia article for "Ethernet Frame", we can find the format of a layer 2 Ethernet frame:

| Ethernet II Frame | MAC Destination | MAC Source | Ethertype | Payload | Frame Check 32‑bit CRC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 Bytes | 6 Bytes | 2 Bytes | 46‑1500 Bytes | 4 Bytes |

Python "raw" ethernet sockets will hand over ethernet frames minus the 4 bytes checksum at the end.

So to put it simply, we will receive:

- 6 bytes destination MAC Address

- 6 bytes source MAC Address

- 2 bytes Ethernet Type Identifier (payload protocol)

- 46‑1500 bytes payload

The minimum ethernet frame length is 64 bytes in total (14 bytes header + 46 bytes payload + 4 bytes checksum).

Payloads that are smaller than 46 bytes will be padded with zeroed (0x00) bytes at the end.

The python socket will automatically add/remove the 4 bytes checksum at the end and it will also automatically add/remove the 0x00 padding at the end of your payload. So be aware of that when you write your code, you might receive less than 60 bytes because there was padding and it has already been removed.

Now let's turn what we have learned into code.

Save this as sniffer.py:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket

import struct

def unpack_ethernet_frame(data):

dest_mac, src_mac, ethertype = struct.unpack('! 6s 6s H', data[:14])

return dest_mac, src_mac, ethertype, data[14:]

ETH_P_ALL = 0x03 # Listen for everything

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

while True:

raw_data, addr = s.recvfrom(65565)

dest_mac, src_mac, ethertype, payload = unpack_ethernet_frame(raw_data)

print(f"[ Frame - Dest: {dest_mac}; Source: {src_mac}; EtherType: {hex(ethertype)} ]")

The integer parameter in recvfrom() is the buffer size.

Since we did not tell the socket which network interface we want to use, it will listen on all interfaces, which is fine for now.

But if you wanted, you could bind the socket to a single interface with:

# Bind socket to a network interface by name

s.bind(("eth0", 0))

# Print basic socket info

print(s.getsockname()) # ('eth0', 3, 0, 1, b"\x08\x00'~\x88\x1f")

# Print all available interfaces

print(socket.if_nameindex()) # [(1, 'lo'), (2, 'eth0')]

If your test network is already pretty noisy, then you might want to bind the socket to your loopback interface (here named 'lo') for now. That would ensure that you only receive localhost traffic.

But enough about interfaces, let's get back to our sniffer.

If we run our code with sudo python3 sniffer.py and open google.com in a web browser, then we will see an output like this:

kali@kali:/tmp/blub$ sudo python3 sniffer.py

[ Frame - Dest: b"\x08\x00'\xa9\xd9b"; Source: b"\x08\x00'~\x88\x1f"; EtherType: 0x800 ]

[ Frame - Dest: b"\x08\x00'\xa9\xd9b"; Source: b"\x08\x00'~\x88\x1f"; EtherType: 0x800 ]

[ Frame - Dest: b"\x08\x00'\xa9\xd9b"; Source: b"\x08\x00'~\x88\x1f"; EtherType: 0x800 ]

[ Frame - Dest: b"\x08\x00'~\x88\x1f"; Source: b"\x08\x00'\xa9\xd9b"; EtherType: 0x800 ]

[ Frame - Dest: b"\x08\x00'\xa9\xd9b"; Source: b"\x08\x00'~\x88\x1f"; EtherType: 0x800 ]

# Press CTRL+C to kill the sniffer

Now that seems to work as intended, but the output of the Ethernet MAC addresses is not exactly pretty.

MAC Address Converter

We want the common hexadecimal MAC Address notation of 11-22-33-aa-bb-cc for the six bytes. So let's add a little MAC Address converter to the top of our python file.

All we need to do is iterate over those six bytes of the MAC address and use the format() function on each.

This format string will do the trick: 02x.

The x means it should be printed as lowercase hex. The 2 indicates it should be at least 2 characters and the 0 tells format() that the output should be padded with zeroes (instead of spaces) if it is only a single hex digit e.g 0a instead of just a.

In the end we just have to join all six formated strings back together with a dash inbetween. Which can be done with the well-named join(...) function:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket

import struct

def unpack_ethernet_frame(data):

dest_mac, src_mac, ethertype = struct.unpack('! 6s 6s H', data[:14])

return dest_mac, src_mac, ethertype, data[14:]

def mac_to_str(data):

octets = []

for b in data:

octets.append(format(b, '02x'))

return "-".join(octets)

ETH_P_ALL = 0x03 # Listen for everything

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

while True:

raw_data, addr = s.recvfrom(65565)

dest_mac, src_mac, ethertype, payload = unpack_ethernet_frame(raw_data)

print(f"[ Frame - Dest: {mac_to_str(dest_mac)}; Source: {mac_to_str(src_mac)}; EtherType: {hex(ethertype)} ]")

We get a nicer print-out:

kali@kali:/tmp/blub$ sudo python3 sniffer.py

[ Frame - Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; EtherType: 0x800 ]

[ Frame - Dest: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Source: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; EtherType: 0x800 ]

[ Frame - Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; EtherType: 0x800 ]

[ Frame - Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; EtherType: 0x800 ]

[ Frame - Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; EtherType: 0x800 ]

Now we can see the MAC addresses of my two VM's. My kali box 08-00-27-7e-88-1f and the router VM 08-00-27-a9-d9-62 talking with each other.

But what is with that EtherType 0x800?

Wikipedia once again comes to the rescue (See also IEEE 802 Numbers):

The EtherType 0x800 indicates that the Ethernet Frame contains an IPv4 payload. Which makes sense, considering I just sent an HTTP request to google.com. HTTP/1.x is usually transmitted via TCP which in turn gets encapsulated in IPv4 or Ipv6 packages.

I have created a dictionary for this so we can easily translate the EtherType values to their human readable names:

Save this as network_constants.py in the same directory.

Creating Structure

Since we will parse a bunch of other protocols, we should create a rudimentary structure that we can use to parse and store the data we receive.

We will create a class for our ethernet frames called EthernetFrame.

Create a new file called ethernet_tools.py:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import struct

from network_constants import ETHER_TYPE_DICT

class EthernetFrame:

def __init__(self, data):

dest_mac, src_mac, ethertype, payload = self.unpack_ethernet_frame(data)

self.DESTINATION = dest_mac

self.SOURCE = src_mac

self.ETHER_TYPE = ethertype

self.PAYLOAD = payload

def unpack_ethernet_frame(self, data):

dest_mac, src_mac, ethertype = struct.unpack('! 6s 6s H', data[:14])

return dest_mac, src_mac, ethertype, data[14:]

def mac_to_str(self, data):

octets = []

for b in data:

octets.append(format(b, '02x'))

return "-".join(octets)

def __str__(self):

ether = hex(self.ETHER_TYPE)

trans = "UNKNOWN"

# Translate EtherType to human readable text

if self.ETHER_TYPE in ETHER_TYPE_DICT:

trans = ETHER_TYPE_DICT[self.ETHER_TYPE]

source = self.mac_to_str(self.SOURCE)

dest = self.mac_to_str(self.DESTINATION)

length = len(self.PAYLOAD)

return f"[ Ethernet - {ether} {trans}; Source: {source}; Dest: {dest}; Len: {length} ]"

Now we can clean up our sniffer.py file a bit:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket

import struct

from ethernet_tools import EthernetFrame

ETH_P_ALL = 0x03 # Listen for everything

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

while True:

raw_data, addr = s.recvfrom(65565)

frame = EthernetFrame(raw_data)

print(frame)

At this point we should have the following files in our working directory:

- sniffer.py

- ethernet_tools.py

- network_constants.py

And our print-outs should look somewhat like this:

kali@kali:/tmp/blub$ sudo python3 sniffer.py

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Len: 52 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Dest: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Len: 52 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Len: 56 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Len: 56 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Dest: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Len: 72 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Dest: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Len: 84 ]

L3: IPv4

Now that we have taken care of Ethernet we can take a look at one of the protocols that will most likely contain valuable information.

Sadly the IPv4 header is a bit more complex than the nice and boring Ethernet header.

| IPv4 Header Bytes |

|---|

| Byte 0 | Byte 1 | Byte 2 | Byte 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Version & IHL | DSCP & ECN | Total Length | |

| Byte 4 | Byte 5 | Byte 6 | Byte 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Identification | Flags & Offset |

| Byte 8 | Byte 9 | Byte 10 | Byte 11 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time To Live | Protocol | Header Checksum | |

| Byte 12 | Byte 13 | Byte 14 | Byte 15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source IP Address |

| Byte 16 | Byte 17 | Byte 18 | Byte 19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Destination IP Address |

| More bytes are used for Options if IHL > 5, otherwise the payload starts here directly. |

Some of these fields are subdivided into smaller fields that do not necessarily fall in line with clean byte borders.

For instance the first byte contains both Version & IHL, which are 4 bits each. The "0" bit here is the left-most bit of the byte.

| Bytes: | Byte 0 | Bits: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content: | Version | IHL | ||||||

And the second byte contains both DSCP (6 bits) and ECN (2 bits):

| Bytes: | Byte 1 | Bits: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content: | DSCP | ECN | ||||||

Byte 6 and 7 contain Flags & Offset. The Flags field is 3 bits, Offset is 13 bits:

| Byte 6 | Byte 7 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flags | Offset | ||||||||||||||

Yes, I know what you are thinking right now. All of this looks a bit overwhelming. Luckily we are only interested in a few of these fields, at least at the moment.

We will only do a rough parsing of these fields and pick out the ones we actually need.

The information we will look at for now is:

- Source IP Address

- Target IP Address

- IHL - Internet Header Length (so we can parse this mess)

- Protocol (so we know what payload this IPv4 packet has)

- Total Length

IP Header Length

The Internet Header Length (IHL) determines the length of the IPv4 header.

The default (minimum) value is 5, which seems a bit inexplicable. But if we read the specification (or wikipedia), then we can figure out that we have to multiply it by 4 and then we get the actual header length:

5 x 4 Bytes = 20 Bytes

This matches the Byte Table I have shown you above. This also means the (optional) Options field, if it exists, always has to be a multiple of 4 bytes (32 bits).

Parsing IPv4

Let's turn what we have learned into code again. We will add a class IPV4 to ethernet_tools.py.

We can copypaste quite a lot of this from the EthernetFrame class with minor adjustments:

from network_constants import ETHER_TYPE_DICT, IP_PROTO_DICT

# ...

# class EthernetFrame omitted

# ...

class IPV4:

ID = 0x0800 # EtherType

def __init__(self, data):

VER_IHL, DSCP_ECN, LEN, ID, FLAGS_OFFSET, TTL, PROTO, CHECKSUM, \

SOURCE, DEST, LEFTOVER = self.unpack_ipv4(data)

# BYTE 2 & 3

self.LENGTH = LEN

# BYTE 9

self.PROTOCOL = PROTO

# BYTE 12 & 13

self.SOURCE = SOURCE

# BYTE 14 & 15

self.DESTINATION = DEST

def unpack_ipv4(self, data):

VER_IHL, DSCP_ECN, LEN, ID, FLAGS_OFFSET, TTL, PROTO, CHECKSUM, \

SOURCE, DEST = struct.unpack("! B B H H H B B H 4s 4s", data[:20])

return VER_IHL, DSCP_ECN, LEN, ID, FLAGS_OFFSET, TTL, PROTO, \

CHECKSUM, SOURCE, DEST, data[20:]

def ipv4_to_str(self, data):

octets = []

for b in data:

octets.append(format(b, 'd'))

return ".".join(octets)

def __str__(self):

proto = hex(self.PROTOCOL)

trans = "UNKNOWN"

# Translate IPv4 payload Protocol to human readable name

if self.PROTOCOL in IP_PROTO_DICT:

trans = IP_PROTO_DICT[self.PROTOCOL]

source = self.ipv4_to_str(self.SOURCE)

dest = self.ipv4_to_str(self.DESTINATION)

return f"[ IPV4 - Proto: {proto} {trans}; Source: {source}; Dest: {dest} ]"

Note that the IP address converter is basically identical to the MAC address coverter, we are just turning the bytes into decimals instead of hex and use a dot as separator instead of a dash.

Now the first order of business should be taking apart the first byte containing VERSION & IHL so we can determine the start of the payload.

You might remember the 0 byte is split perfectly in half with each value being 4 bits each:

| Bytes: | Byte 0 (IPv4) | Bits: | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content: | Version | IHL | ||||||

In order to take this apart we can use simple bit-wise operators.

Bit-Shifting Detour

The bit-wise AND (&) operator does pretty much what we want. Let's assume our Input Byte has the binary value 10101010

If we only want the right most 4 bits, then we can apply an AND with only the right four bits set to True 00001111

1010 1010

& 0000 1111

---------

= 0000 1010

As Python code:

VER_IHL = 0b10101010

IHL = VER_IHL & 0b00001111 # 00001010

Or more concise with Hex notation:

VER_IHL = 0b10101010

IHL = VER_IHL & 0x0F # 00001010

And done. We have the IHL.

Now we need to extract the VERSION value. The process is the same for the 4 bits on the left:

1010 1010

& 1111 0000

---------

= 1010 0000

But since the value of Binary is read from right-to-left we will have to get rid of the 4 zeroed bits on the right. We can accomplish this by shifting everything 4 bits to the right with the shift operator >>.

1010 0000 >> 4

---------

= 1010

VER_IHL = 0b10101010

VERSION = (VER_IHL & 0xF0) # 10100000

VERSION = VERSION >> 4 # 00001010

Since the four right-most bits effectively get deleted by the shift anyway, we can just shorten this to:

VER_IHL = 0b10101010

VERSION = VER_IHL >> 4 # 00001010

We can apply this to our IPV4 class init function:

def __init__(self, data):

VER_IHL, DSCP_ECN, LEN, ID, FLAGS_OFFSET, TTL, PROTO, CHECKSUM, \

SOURCE, DEST, LEFTOVER = self.unpack_ipv4(data)

# Byte 0

self.VERSION = VER_IHL >> 4

self.IHL = VER_IHL & 0x0F

# BYTE 2 & 3

self.LENGTH = LEN

# BYTE 9

self.PROTOCOL = PROTO

# BYTE 12 & 13

self.SOURCE = SOURCE

# BYTE 14 & 15

self.DESTINATION = DEST

options_len = 0

if self.IHL > 5:

options_len = (self.IHL - 5) * 4

self.OPTIONS = LEFTOVER[:options_len]

self.PAYLOAD = LEFTOVER[options_len:]

A bit of Color in my Life

Let's plug our new IPV4 capabilities into our sniffer.py:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket

import struct

from ethernet_tools import EthernetFrame, IPV4

ETH_P_ALL = 0x03 # Listen for everything

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

while True:

raw_data, addr = s.recvfrom(65565)

# Ethernet

frame = EthernetFrame(raw_data)

print(str(frame))

# IPV4

if frame.ETHER_TYPE == IPV4.ID:

ipv4 = IPV4(frame.PAYLOAD)

print("└─ " + str(ipv4))

Let's run it and visit google.com in our browser again:

kali@kali:/tmp/blub$ sudo python3 sniffer.py

[ Ethernet - 0x806 Address Resolution Protocol (ARP); Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Len: 28 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x806 Address Resolution Protocol (ARP); Source: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Dest: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Len: 46 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Len: 280 ]

└─ [ IPV4 - Proto: 0x6 TCP; Source: 10.0.2.4; Dest: 172.217.16.196 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Len: 83 ]

└─ [ IPV4 - Proto: 0x6 TCP; Source: 10.0.2.4; Dest: 172.217.16.196 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Dest: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Len: 52 ]

└─ [ IPV4 - Proto: 0x6 TCP; Source: 172.217.16.196; Dest: 10.0.2.4 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Dest: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Len: 199 ]

└─ [ IPV4 - Proto: 0x6 TCP; Source: 172.217.16.196; Dest: 10.0.2.4 ]

[ Ethernet - 0x800 Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4); Source: 08-00-27-7e-88-1f; Dest: 08-00-27-a9-d9-62; Len: 52 ]

└─ [ IPV4 - Proto: 0x6 TCP; Source: 10.0.2.4; Dest: 172.217.16.196 ]

It works, we can see my Kali VM (10.0.2.4) communicating with a google server (172.217.16.196).

But this becomes a bit of a white snowstorm of text. Let us add some colors.

Most modern terminals on Linux and Windows support colored text printing:

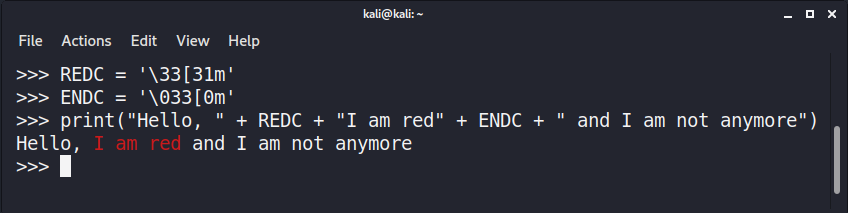

kali@kali:~$ python3

Python 3.8.3 (default, May 14 2020, 11:03:12)

[GCC 9.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

>>> REDC = '\33[31m'

>>> ENDC = '\033[0m'

>>> print("Hello, " + REDC + "I am red" + ENDC + " and I am not anymore")

You see, all it takes is putting text between two escaped control sequences. The first one sets the text color and the second one lets the terminal know you wish to return to normal.

I have created a small colorizing script, so you don't have to:

Save this as colors.py in your working directory.

Let us give our IPv4 packets a nice blue tint in sniffer.py:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket

import struct

from ethernet_tools import EthernetFrame, IPV4

from colors import *

ETH_P_ALL = 0x03 # Listen for everything

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

while True:

raw_data, addr = s.recvfrom(65565)

# Ethernet

frame = EthernetFrame(raw_data)

print(str(frame))

# IPV4

if frame.ETHER_TYPE == IPV4.ID:

ipv4 = IPV4(frame.PAYLOAD)

print(blue("└─ " + str(ipv4)))

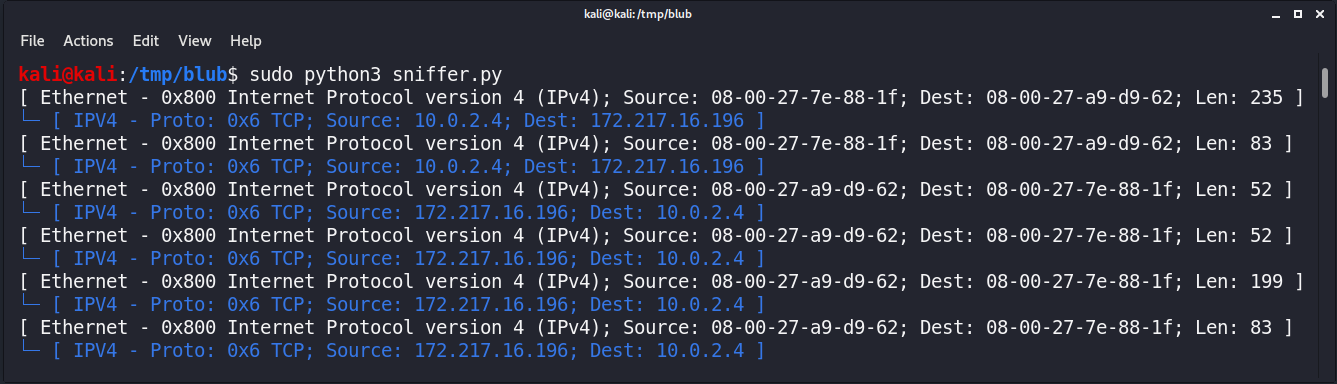

Let's run that again:

That's make it a bit easier to distinguish.

L4: UDP

We move up another layer. We will start with UDP (User Datagram Protocol) since the protocol is pleasantly simple.

You know the drill at this point:

| UDP Datagram Header |

|---|

| Byte 0 | Byte 1 | Byte 2 | Byte 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source Port | Destination Port |

| Byte 4 | Byte 5 | Byte 6 | Byte 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | Checksum |

The checksum is optional when used with IPv4 and mandatory when used with IPv6.

The Source Port can be unused, but the Destination Port is required.

Source Port and Checksum are all 0x00 if unused. So the length of the header should be consistent either way.

The length field is for the total datagram (header + payload).

Extend ethernet_tools.py again with our UDP class:

# ...

class UDP:

ID = 0x11 # IPv4 Protocol ID

def __init__(self, data):

SOURCE, DEST, LEN, CHKSUM, LEFTOVER = self.unpack_udp(data)

self.SOURCE_PORT = SOURCE

self.DEST_PORT = DEST

self.LENGTH = LEN

self.CHECKSUM = CHKSUM

self.PAYLOAD = LEFTOVER

def unpack_udp(self, data):

SOURCE, DEST, LEN, CHKSUM = struct.unpack("! H H H H", data[:8])

return SOURCE, DEST, LEN, CHKSUM, data[8:]

def __str__(self):

return f"[ UDP - Source Port: {self.SOURCE_PORT}; Destination Port: {self.DEST_PORT}; LEN: {self.LENGTH} ]"

After wrestling with IPv4 this feels almost too easy.

Let us include this in our sniffer.py with a nice yellow color:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket

import struct

from ethernet_tools import EthernetFrame, IPV4, UDP

from colors import *

ETH_P_ALL = 0x03 # Listen for everything

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

while True:

raw_data, addr = s.recvfrom(65565)

# Ethernet

frame = EthernetFrame(raw_data)

print(str(frame))

# IPV4

if frame.ETHER_TYPE == IPV4.ID:

ipv4 = IPV4(frame.PAYLOAD)

print(blue("└─ " + str(ipv4)))

# UDP

if ipv4.PROTOCOL == UDP.ID:

udp = UDP(ipv4.PAYLOAD)

print(yellow(" └─ " + str(udp)))

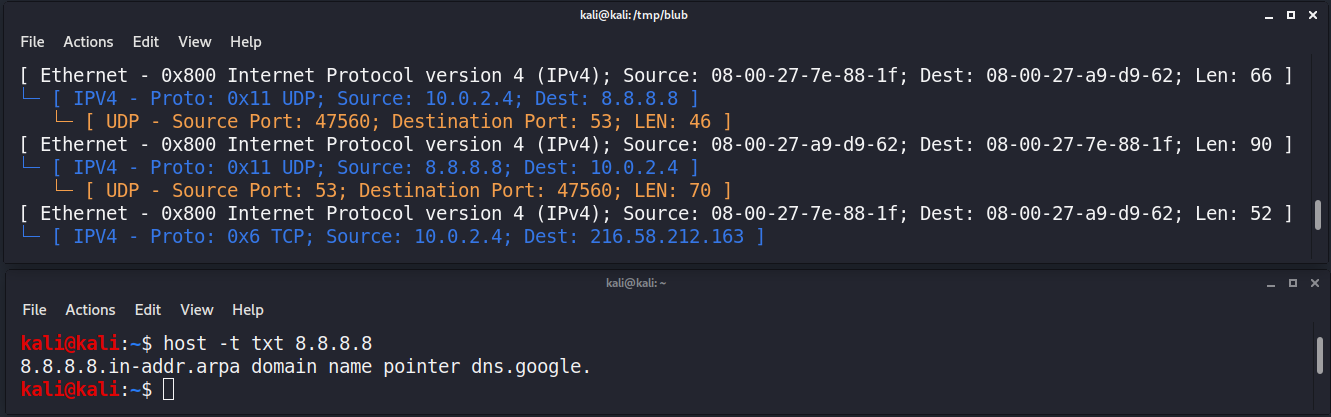

We can trigger a UDP communication by performing a random DNS request to a public DNS server (e.g. 8.8.8.8 or 1.1.1.1).

kali@kali:~$ host -t txt 8.8.8.8

8.8.8.8.in-addr.arpa domain name pointer dns.google.

This seems to have worked. The standard DNS server port is 53 by the way.

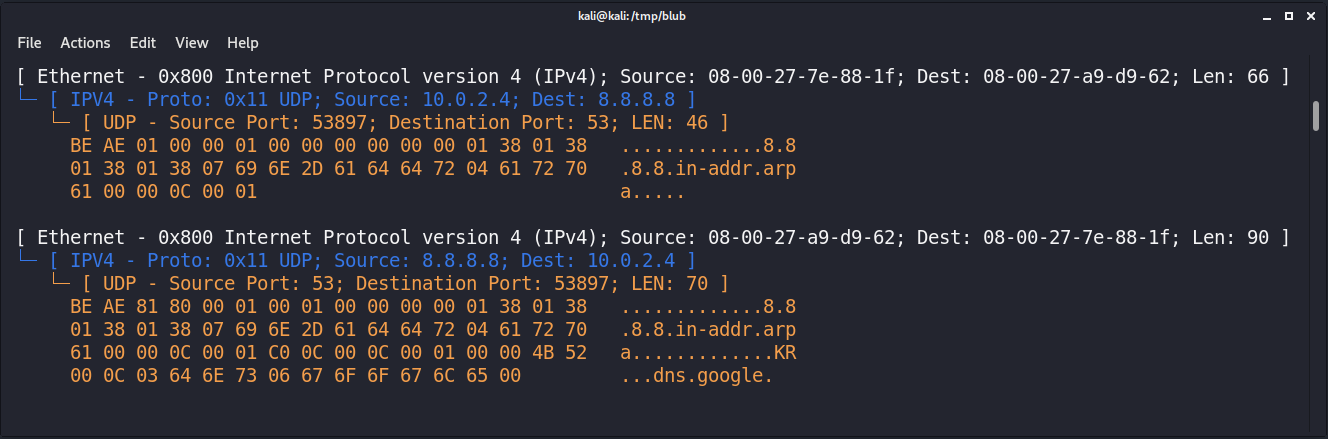

Dumping the Hexes

It's probably overdue that we take a look at the actual content of our payloads.

The problem is that the data sent via UDP or TCP is not always human readable.

Therefore we will create a simple hex dump function.

The requirements are simple enough:

- Print 16 bytes as hex

- Print the same 16 bytes, but as alphanumeric characters, or if they are not printable as dot "."

- Start a new line

- Repeat until you run out of bytes

This should be easy enough if we remember that printable characters live in the integer range [32 - 126] and the python standard function chr(i) will turn your integer into a string character for you. The escape sequence for a new line is "\n".

We will add this function to ethernet_tools.py:

#...

def hexdump(bytes_input, left_padding=0, byte_width=16):

current = 0

end = len(bytes_input)

result = ""

while current < end:

byte_slice = bytes_input[current : current + byte_width]

# indentation

result += " " * left_padding

# hex section

for b in byte_slice:

result += "%02X " % b

# filler

for _ in range(byte_width - len(byte_slice)):

result += " " * 3

result += " "

# printable character section

for b in byte_slice:

if (b >= 32) and (b < 127):

result += chr(b)

else:

result += "."

result += "\n"

current += byte_width

return result

Plug that into our sniffer.py again:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket

import struct

from ethernet_tools import EthernetFrame, IPV4, UDP, hexdump

from colors import *

ETH_P_ALL = 0x03 # Listen for everything

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

while True:

raw_data, addr = s.recvfrom(65565)

# Ethernet

frame = EthernetFrame(raw_data)

print(str(frame))

# IPV4

if frame.ETHER_TYPE == IPV4.ID:

ipv4 = IPV4(frame.PAYLOAD)

print(blue("└─ " + str(ipv4)))

# UDP

if ipv4.PROTOCOL == UDP.ID:

udp = UDP(ipv4.PAYLOAD)

print(yellow(" └─ " + str(udp)))

print(yellow(hexdump(udp.PAYLOAD, 5)))

Looks like we are getting somewhere.

L4: TCP

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) is probably the most common protocol for communicating via IPv4. And also quite a bit more complex than UDP.

Here is the Byte Table for the TCP header:

| TCP Segment Header |

|---|

| Byte 0 | Byte 1 | Byte 2 | Byte 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Source Port | Destination Port |

| Byte 4 | Byte 5 | Byte 6 | Byte 7 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence number |

| Byte 8 | Byte 9 | Byte 10 | Byte 11 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acknowledgment number (if ACK set) |

| Byte 12 | Byte 13 | Byte 14 | Byte 15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Offset & Flags | Window Size |

| Byte 16 | Byte 17 | Byte 18 | Byte 19 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Checksum | Urgent pointer (if URG set) |

| More bytes are used for Options if Data Offset > 5, otherwise the payload starts here directly. |

This seems eerily similar to IPv4, especially the optional Options field.

But unlike IPv4 there is only one field that contains smaller fields that do not follow exact byte borders: Data Offset & Flags.

| Byte 12 | Byte 13 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Offset | Reserved (0 0 0) |

N S |

C W R |

E C E |

U R G |

A C K |

P S H |

R S T |

S Y N |

F I N |

|||||

We can use bit-shifting again in order to get these flags and the Offset. Flags are only one bit each, so we can use the AND mask 0x01.

FIN = OFFSET_FLAGS & 0x01

SYN = (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 1) & 0x01

RST = (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 2) & 0x01

PSH = (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 3) & 0x01

ACK = (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 4) & 0x01

URG = (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 5) & 0x01

ECE = (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 6) & 0x01

CWR = (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 7) & 0x01

NS = (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 8) & 0x01

OFFSET = OFFSET_FLAGS >> 12 # 4 Bits

Since each flag is only one bit (False = 0 or True = 1), we can turn them into booleans if we want:

SYN = bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 1) & 0x01 )

We will store these booleans in a dictionary for convenience. If you want to save space, then you can just keep them in the original integer and extract them whenever needed, but in this tutorial we go the lazy route and actually store them.

Here is our Flags dictionary:

self.FLAGS = {

"FIN" : bool( OFFSET_FLAGS & 0x01 ),

"SYN" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 1) & 0x01 ),

"RST" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 2) & 0x01 ),

"PSH" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 3) & 0x01 ),

"ACK" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 4) & 0x01 ),

"URG" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 5) & 0x01 ),

"ECE" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 6) & 0x01 ),

"CWR" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 7) & 0x01 ),

"NS" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 8) & 0x01 )

}

With the Flags and Offset figured out, we can hack together a TCP class with parts of our already existing IPV4 and UDP classes:

In ethernet_tools.py:

#...

class TCP:

ID = 0x06 # IPv4 Protocol ID

def __init__(self, data):

SRC, DEST, SEQ, ACK_NUM, OFFSET_FLAGS, WIN_SIZE, \

CHKSUM, URG_PTR, LEFTOVER = self.unpack_tcp(data)

# Byte 0 & 1

self.SOURCE_PORT = SRC

# Byte 2 & 3

self.DEST_PORT = DEST

# Bytes 4, 5, 6, 7

self.SEQUENCE_NUM = SEQ

# Bytes 8, 9, 10, 11

self.ACK_NUM = ACK_NUM

# Bytes 12 & 13

self.FLAGS = {

"FIN" : bool( OFFSET_FLAGS & 0x01 ),

"SYN" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 1) & 0x01 ),

"RST" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 2) & 0x01 ),

"PSH" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 3) & 0x01 ),

"ACK" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 4) & 0x01 ),

"URG" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 5) & 0x01 ),

"ECE" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 6) & 0x01 ),

"CWR" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 7) & 0x01 ),

"NS" : bool( (OFFSET_FLAGS >> 8) & 0x01 )

}

self.OFFSET = OFFSET_FLAGS >> 12

# Byte 14 & 15

self.WINDOW_SIZE = WIN_SIZE

# Byte 16 & 17

self.CHECKSUM = CHKSUM

# Byte 18 & 19

self.URGENT_POINTER = URG_PTR

options_len = 0

if self.OFFSET > 5:

options_len = (self.OFFSET - 5) * 4

self.PARAMS = LEFTOVER[:options_len]

self.PAYLOAD = LEFTOVER[options_len:]

def unpack_tcp(self, data):

SRC, DEST, SEQ, ACK_NUM, OFFSET_FLAGS, WIN_SIZE, \

CHKSUM, URG_PTR = struct.unpack("! H H I I H H H H", data[:20])

return SRC, DEST, SEQ, ACK_NUM, OFFSET_FLAGS, WIN_SIZE, \

CHKSUM, URG_PTR, data[20:]

def __str__(self):

active_flags = []

for key in self.FLAGS:

if self.FLAGS[key]:

active_flags.append(key)

flags_str = ', '.join(active_flags)

res = "[ TCP - "

res += f"Source Port: {self.SOURCE_PORT}; "

res += f"Destination Port: {self.DEST_PORT}; "

res += f"Flags: ({flags_str}); "

res += f"Sequence: {self.SEQUENCE_NUM}; "

res += f"ACK_NUM: {self.ACK_NUM} "

res += "]"

return res

In sniffer.py:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import socket

import struct

from ethernet_tools import EthernetFrame, IPV4, UDP, TCP, hexdump

from colors import *

ETH_P_ALL = 0x03 # Listen for everything

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_PACKET, socket.SOCK_RAW, socket.htons(ETH_P_ALL))

while True:

raw_data, addr = s.recvfrom(65565)

# Ethernet

frame = EthernetFrame(raw_data)

print(str(frame))

# IPV4

if frame.ETHER_TYPE == IPV4.ID:

ipv4 = IPV4(frame.PAYLOAD)

print(blue("└─ " + str(ipv4)))

# UDP

if ipv4.PROTOCOL == UDP.ID:

udp = UDP(ipv4.PAYLOAD)

print(yellow(" └─ " + str(udp)))

print(yellow(hexdump(udp.PAYLOAD, 5)))

# TCP

elif ipv4.PROTOCOL == TCP.ID:

tcp = TCP(ipv4.PAYLOAD)

print(green(" └─ " + str(tcp)))

print(green(hexdump(tcp.PAYLOAD, 5)))

That should do it.

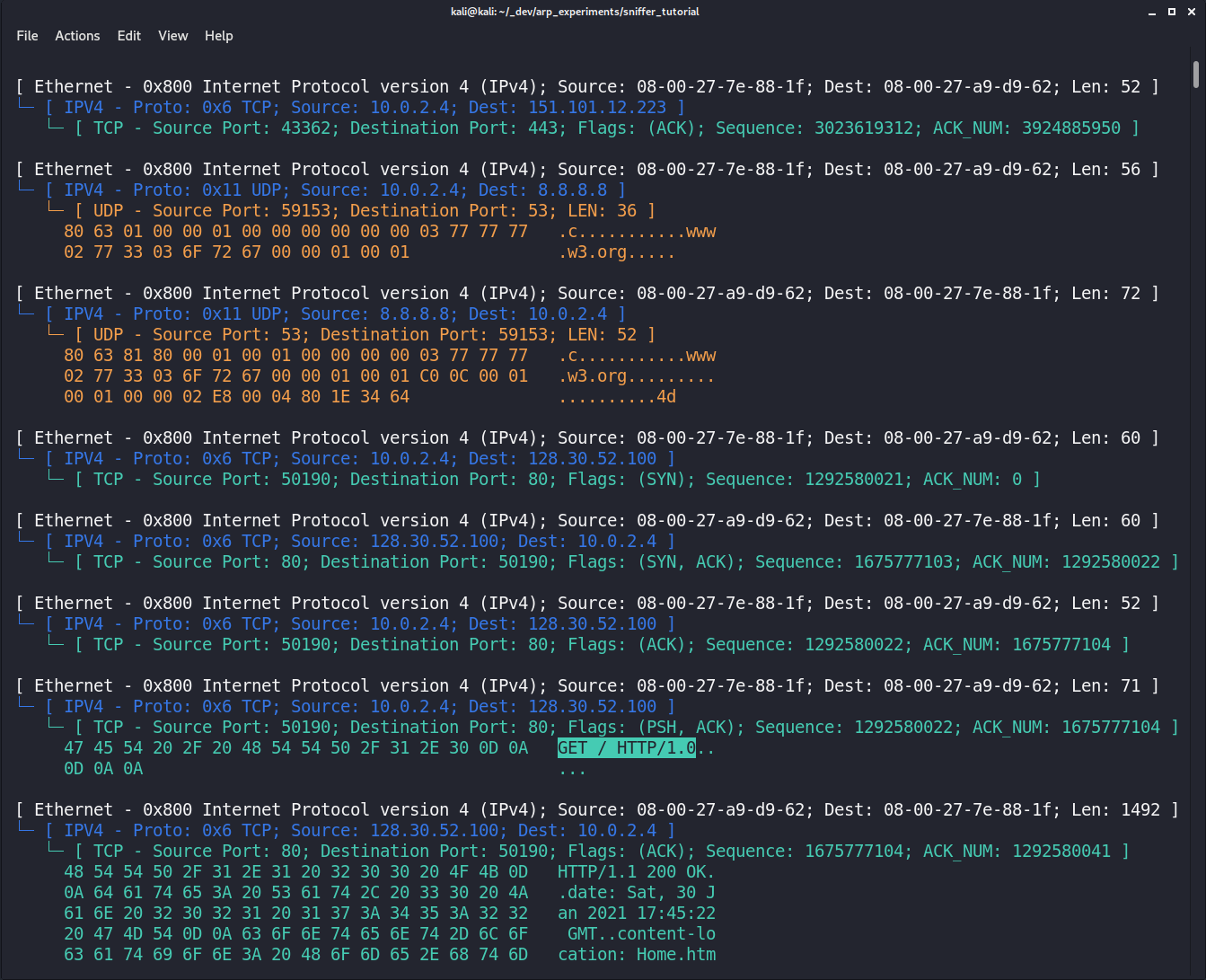

For instance, now we can capture the entirety of an HTTP communication.

Let's send an HTTP request to the W3C website:

echo -e "GET / HTTP/1.0\r\n\r\n" | nc www.w3.org 80

This is how the capture looks like:

Seems to work!

Comparing the header values and payloads in Wireshark shows that our parsing appears to be accurate.

That's about as far as we will go in this tutorial when it comes to protocols.

Improvements and Some Use Cases

That concludes this tutorial, but here are some afterthoughts.

Of course you can implement data structures for some other common protocols. But the problem we now have is rather too much information.

So building some filters to only display certain protocols and network interfaces would be a good idea. You could add some command line options in order to control the output.

And we have done absolutely zero error handling so far. I would recommend simply discarding any Ethernet Frame that causes an error and move on to the next iteration:

while True:

try:

raw_data, addr = s.recvfrom(65565)

# Ethernet

frame = EthernetFrame(raw_data)

print(str(frame))

# ...

except Exception as e:

print(red("[ Error: Failed To Parse Frame Data]"))

print(red(str(e)))

It might also be worthwhile to create the option to assemble TCP segments to get the complete message and log them to output files.

Sniffing for Info

One easy thing we can do is automatically search TCP/UDP payloads for certain byte sequences or clear text strings, for instance our favorite one: "password".

You might want to search for all common character encodings and not just look for the UTF-8 version.

If you want to search for several byte sequences or strings at the same time, then I recommend using something like the Aho–Corasick algorithm.

Man-in-the-Middle

It should be easy to extend our data structures so they can be turned back into valid byte sequences. struct works in both directions:

def unpack_udp(data):

SOURCE, DEST, LEN, CHKSUM = struct.unpack("! H H H H", data[:8])

return SOURCE, DEST, LEN, CHKSUM, data[8:]

def pack_udp(SOURCE, DEST, LEN, CHKSUM, data):

header = struct.pack("! H H H H", SOURCE, DEST, LEN, CHKSUM)

return header + data

Most of the time you will have to recalculate the header checksums though, if you change any of the headers or payloads.

You can use this as the basis for a Spoofing attack (e.g. ARP spoofing).

Silent Profiling

You can create profiles of machines in the neighborhood.

Keep track of MAC Addresses and associate IP Addresses and open Port numbers with them. This might be an alternative to noisy port scanners.

Due to switching, this might be not very effective though, unless you use some kind of spoofing. Wireless LAN is a different can of worms that I won't open here.

FIN ACK

Well that's it, have fun!

Here are all the files:

Or summarized as a Github repository (branch "tutorial").